Japanese animation, known colloquially as anime, and its related counterpart manga, or Japanese comic books, have recently gained widespread popularity in Canada and around the world. Anime and manga in first appeared in North America in the late 1980s. Facilitated by globalization and the growth of the internet, a steadily increasing amount of such material from Japan has made its way to Canada and the United States. Anime has become a visible presence on Western television (including the Fox Network’s regular Saturday morning rotation) and manga is now readily available in large chain bookstores across Canada. Many of the more dedicated fans of these Japanese products regularly attend anime conventions. Toronto is hosts two major conventions, which can draw crowds of nearly 10,000 people, primarily high school and college students.

On the weekend of November 25 – 27, 2005, a new convention was held at the Doubletree International Plaza Hotel in Toronto called “Con no Baka”, literally translated as “Convention of Fools”. The carnivalesque elements inherent in conventions become immediately apparent not only from this title, but from the mascot of the event: a girl drawn in the anime style wearing the outfit of a medieval court jester, a figure common in Carnival (Fig. 1). Upon entering the hotel, a noticeable change was apparent in the body language and speech of the attendees, compared to those on the street outside. The majority of the participants in the event spoke extremely animatedly with grandiose gestures and in unusually loud voices, and also employed a normally unacceptable level of profanity, yelling, and screaming. A much higher level of physical contact was evident as the fans interacted in a seemingly violent but friendly way. For example, a common sight during the opening hours of the convention was the “glomp”, a powerful and crushing embrace delivered from a running start designed to knock the recipient over, but also to show extreme affection. This excessive action could be enacted on both strangers and acquaintances alike without repercussion. Upon inquiry, several fans recognized that such behaviour was acceptable only within the convention, and that they would never act in such a way anywhere else: “At con[vention]s you can do things that are far outside of general social restrictions, and regular people don’t have the same kind of outlet”, one attendee stated. Such free intermingling of bodies is indicative of the Bakhtinian Carnival, as is the obviously extreme body language and interaction (Clark and Holquist, 1984).

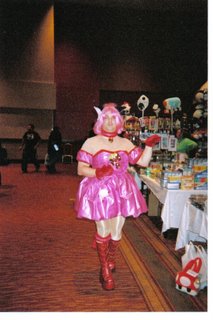

One of the most common features of the anime convention is known as “costume play”, usually abbreviated to “cosplay”, where fans spend a great deal of effort and expense to create and wear elaborate costumes of characters from their favourite anime or manga. Cosplays can consist of brightly coloured wigs, detailed props, and can be quite revealing, as well as drastically different from anything one might seen the average person. The fans wearing the most outrageous and daring outfits are the stars of the convention, and receive much attention from admirers throughout the course of the weekend (Fig. 2). Such costumes are an excellent illustration of the celebration of the body and of the fluid concept of identity found in the carnivalesque (Wills in Hirschkop and Shepherd, 1989). A woman visiting the hotel for an unrelated event compared the scene before her to Halloween, another recognizably carnivalesque event. The transgression of social norms and reversal of status so fundamental to Carnival may be seen in “crossplay” (cross-dress cosplay), another type of costuming common at conventions in which men and women adopt the costumes and mannerisms of a character from the opposite sex (Fig. 3). Prizes were awarded to those with the strangest apparel as well as the best “crossplayer”, and several panel discussions were held on the methods and execution of cosplay, enculturating newer fans into the practice.

As described by Clair Wills, carnivalesque events are renowned for their openness and for publicizing what would normally be considered private and not acceptable for conversation, depiction, or enactment (Wills in Hirschkop and Shepherd). At Con no Baka, young females could be found in hallways and panel rooms openly discussing and sharing yaoi, or graphic male-male homosexual pornography, without any care for who might happen to overhear or disapprove. Other examples of tabooed or delicate issues of sexuality were proudly displayed throughout the hotel, including gay and lesbian interaction and bondage. The staff at both the booths representing Gaylaxicon (the international science fiction/fantasy convention for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered fans) and Toronto Trek (the oldest and most established convention in Ontario) agreed that the community found at conventions is a great deal more accepting of all forms of sexual orientation. The mere existence of an event like Gaylaxicon speaks of the high ratio of fans in the community who ascribe to what would traditionally be considered an “unconventional” lifestyle.

Outside of the convention, the majority of fans at Con no Baka attend middle or high school or a post-secondary institution and work unrewarding part-time jobs, thus occupying positions with very low social, economic, or political status or influence. Due to this fact, the carnivalesque dissolution of distinctions of class and displacement of social force would indeed be very appealing to such a disenfranchised group. One teenage fan proudly declared, “Here, we have the power”. In the carnivalesque convention space, standard economic or political status has absolutely no meaning, and those formerly marginalized groups move to the forefront and control the events that occur (Bakhtin, 1984). As argued by communication theorist Henry Jenkins (1992), a new hierarchy appears in the fan world, and finds the most creative fan producers as the highest in status. The most admired members of the fan community at Con no Baka were the authors of successful “fanfiction” (fan published stories based on the characters or plot of an anime or manga), the highly skilled cosplayers, and the creators of the most technically challenging and aesthetically pleasing anime music videos (or AMVs). Jenkins recognized this role of fanfiction in his studies on science fiction fan culture: “…fan publishing constitutes an alternate source of status, unacknowledged by the dominant social and economic systems but personally rewarding nevertheless” (Jenkins, p. 159). Individuality and inventiveness were the main factors in gaining power in the fan hierarchy, as one cosplayer pointed out: “It doesn’t matter how much money you have, only how creative your costume is.”

Cultural capital in the fan world could also be achieved through knowledge, as fans that are able to speak Japanese or were familiar with the most intimate details of a particular show, author, or actor are deferred to as authorities on issues of debate. The only openly derided members visible at the convention were the newest fans, as they are assumed to have the least knowledge and held the lowest position in the fan hierarchy. Many fans mentioned a group they called the “elitists”, who openly scorn those who mispronounce Japanese words or err in their knowledge of the media, the only open discrimination that was observed to occur during the course of the event.

It must be noted, however, that while knowledge and creative production do grant some fans slightly more status than others, the hierarchy is very vague and there is apparent social mobility. Carnival is utopian and egalitarian in the extreme, and focuses on brotherhood and universalism (Bakhtin). Even if one fan were to gain status based on their creativity, they are not granted any special privileges and have no power over others. Equality and fairness appeared to be of special concern to the fans at the convention, as at panel discussion the moderator would make a special effort to allow younger fans or the soft-spoken to include their thoughts, even if they had not put up their hand. A vendor at the booth for a popular Toronto comic store affirmed that simply being a fan was all that was of importance at a convention, because all fans are “looked down upon equally by others”. Another fan said, “Everyone is united by their shared geekiness… You may have no idea what their name is or where they come from, but … we’re all geeks together”, emphasizing the egalitarianism and communal atmosphere of the convention.

While the freedom of the convention space was esteemed by all that attended Con no Baka, such parity and openness is only temporary. Bakhtin explained Carnival’s reversal and transgression as a provisional release, where the inferior are momentarily elevated to allow the traditional hierarchy to remain intact and continue to prevail over the potentially anarchistic lower orders (Bakhtin in Clark and Holquist, 1984). Although fans from across southern Ontario gather together in a utopian community, conventions only occur for at most three days, and Con no Baka was cancelled after only two due to a dispute with the hotel. Once a fan steps outside the convention space, they re-adopt all the traditional norms they had previously left behind. The dramatic gesticulations and speech are abandoned, costumes are exchanged for street clothes, and each attendee returns to their separate home.

In addition, the communal environment of the convention also masks its fundamentally capitalistic roots. The primary action to take place at Con no Baka was shopping, with the Dealer’s Room as the largest and busiest area of the entire event; it was the first place to visit upon arrival, and the last place to explore before departure. Although many fans pointed to participating in the community or meeting new friends as the most important factor in attending a convention, the overwhelming majority answered that they attended the convention for the shopping. Members of an anime club from New York State underwent a seven-hour bus trip simply to shop at Con no Baka.

For those involved in the anime subculture, the convention is the place in which they are able to freely embrace an alternate society; one in which age, gender, sexual orientation, and other traditional status indicators have no bearing on one’s position. Individuality and creativity were honoured, but fans were also able to enjoy an unprecedented level of equality amongst their peers that they are not able to experience outside of the event. The convention also displayed all the visible markers of a Bakhtinian Carnival, through the spectacle of the body language and speech of the attendees, their costumes, and their interactions with one another. However much the fans valued their openness and equality in direct opposition to the outside world, the events at Con no Baka remained grounded in capitalism and are only temporary, with no power whatsoever to affect any real change on society.

Appendix:

Illustrations

Figure 1: The Con no Baka mascot dressed as a court jester.

Figure 2: One of the award-winning costumes at the convention.

Figure 3: An example of “crossplay”.

Works Cited

Clark, Katerina and Holquist, Michael. Mikhail Bakhtin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

Bakhtin, Mikhail Mikhailovich. Rabelais and His World. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1984.

Hirschkop, Ken, and Shepherd, David, eds. Bakhtin and Cultural Theory. New York: Manchester University Press, 1989.

Jenkins, Henry. Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. New York: Routledge, 1992.

No comments:

Post a Comment